It pains Tim Odegard that four decades after a misguided approach to diagnosing dyslexia kept him from getting help in school, thousands of children across the U.S. are needlessly suffering for the same reason.

During the initial weeks of first grade, Odegard’s struggles with reading went undetected as he memorized words that classmates read aloud before him. The strategy worked so well that his teacher moved him to the position of “first reader.” It then became apparent that the six-year-old not only wasn’t the strongest reader in the class—he couldn’t read at all. The teacher dispatched him to a low-skill group. “It just kind of went downhill from there,” Odegard, now 47, recalled.

Through sheer determination and reliance on his prodigious memory, Odegard eventually memorized enough words to get by and earned decent grades, although they would never come easily. “I compensated for my reading and spelling problems by staying up until 1 or 2 a.m. to get things done,” he said. He never received extra help or special education services from his Houston-area school district. Instead, a couple of teachers seemed to doubt his intelligence. When Odegard was the first student in his school to solve a complex murder mystery puzzle, one of them said he must have guessed.

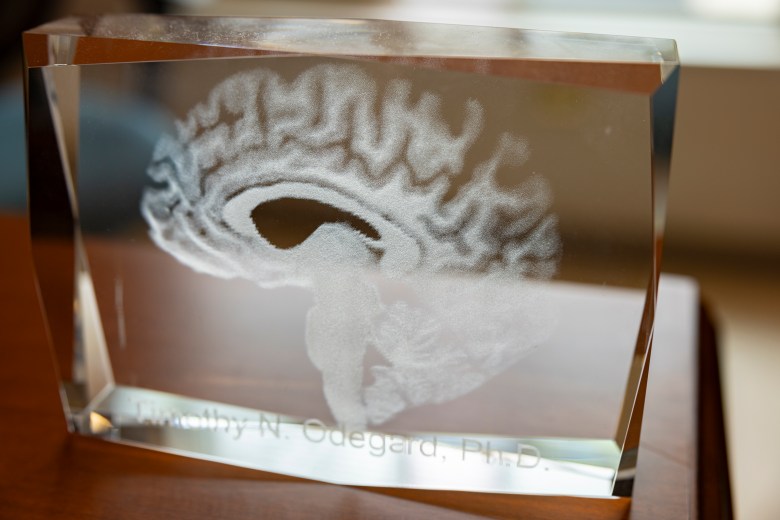

It wasn’t until he was in his late 20s that Odegard came to understand why his teachers thought so poorly of his abilities. In 2004, as a new Ph.D., he told his mother that the National Institutes of Health had awarded him a postdoctoral fellowship to study dyslexia, a condition he’d long suspected he had. She shared that when he was in third grade, school officials had used a so-called discrepancy model that compared intelligence quotient (IQ) with reading performance to rule that he didn’t have a learning disability.

“I was thought to be too stupid to be dyslexic,” said Odegard, now editor in chief of the Annals of Dyslexia and chair of excellence in dyslexic studies at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

Up to around 20 percent of the U.S. population has dyslexia, a neurological condition that makes it difficult to decipher and spell written words. Someone with the disability might omit short words such as “and” and “the” while reading aloud, for example, or read “dog” as “god”—even if they speak normally in conversation. The condition impedes a person’s ability to process written information and can negatively affect their career and well-being. Yet only a fraction of affected students get a dyslexia diagnosis or the specialized assistance that can help them manage their difficulty reading.

One reason so many diagnoses are missed is that thousands of schools in the U.S. continue to use an iteration of the discrepancy model to test children for learning disabilities. Moreover, for a multitude of reasons, including biases in IQ tests, a disproportionate number of those diagnosed—and helped—have been white and middle- to upper-class.

“It’s unfair, it’s discriminatory, and it disadvantages already economically disadvantaged kids,” said Jack Fletcher, co-founder of the Texas Center for Learning Disabilities in Houston and one of the first scientists to question the discrepancy model’s validity.

The model has shaped decades of policy regarding whose literacy is considered vital and worthy of extra help and investment—and whose is not. It is rooted in long-standing misconceptions about dyslexia. Reforming how the condition is defined and diagnosed could help many more children learn to read.

Speaking comes naturally to most children, being a gift of human evolution, but reading and writing are inventions that must be consciously and painstakingly learned. No one is born with neural circuits for connecting the sounds of speech to squiggles on paper. Instead, when someone learns to read, their brain improvises, splicing and joining sections of preexisting circuits for processing vision and speech to form a new “reading circuit.” To read the (written) word “dog,” for example, a typical brain will disaggregate the word into its constituent letters, “d,” “o” and “g,” and then summon from memory the sound fragments, or phonemes, associated with each letter. It aggregates these phonemes into the sound “dog” and retrieves the meaning of the word that matches that sound. Most brains eventually learn to do all these steps so fast that the action seems automatic. Some written words become so familiar that the speech circuit eventually gets bypassed, so that there is a direct association between the word as seen on paper or on a screen and its meaning.

Because human brains are organized in diverse ways, some people’s reading circuits end up being inefficient. Dyslexia is the most common reading disability. People with the condition, which is partly linked to genetics, often have less gray matter and brain activity in the parietotemporal region of the brain’s left hemisphere, associated with connecting the sounds of speech to the shapes of printed text.

The severity and manifestations of dyslexia can vary from person to person, but children with the learning disability benefit most from early help with explications of the sound structures underlying words. For those who continue to struggle in school, the ideal instruction is one-on-one or in a small group with a trained teacher who provides intensive and systematic assistance in making connections between written words and sounds. Learning the rules—and the many, many exceptions—of the English language is particularly important, because children with dyslexia are typically unable to pick them up through mere exposure to text. The letter “a” can be pronounced five different ways in English, whereas in Spanish, for instance, vowels almost always have the same pronunciation.

With the right kind of instruction, most children with dyslexia can learn how to read. In part because of an accident of scientific history, however, this essential assistance has been far more available to kids who score higher on IQ and other cognitive tests. An early case report of dyslexia, published in the British Medical Journal in 1896, helped to define the disorder as an unexpected deficit in otherwise “bright” children. The study described a 14-year-old referred to as Percy F. “He has always been a bright and intelligent boy, quick at games, and in no way inferior to others,” wrote the doctor who examined Percy, “yet in writing from dictation he comes to grief over any but the simplest words.”

That incipient definition characterized a lot of early thinking about dyslexia. It was inadvertently codified in school systems through influential studies led by British psychiatrists Michael Rutter and William Yule on the Isle of Wight in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Rutter and Yule are well regarded for being among the first in the field to focus deeply on children and for their groundbreaking work in autism and post-traumatic stress disorder. When devising a definition of “reading disability” based on the population of nine- to 11-year-olds on the island, the researchers distinguished between poor readers who read at levels predicted by their IQs and those who did not, looking for evidence of dyslexia only in those in the latter group.

The studies came just as the U.S. was creating its own special education categories and definitions to prepare for the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act in 1975. When it came to learning disabilities, experts relied heavily on the idea that for a learning disability to be present, reading performance had to fall short of IQ.

Guidelines put out by the U.S. government in 1977 asked that schools look for a “severe discrepancy between levels of ability and achievement” when screening children for learning disabilities. Thus, a child’s IQ scores, which rank cognitive abilities such as reasoning, began to play an outsize role in determining countless students’ educational fates. Specifically, if the IQ score wasn’t high enough and, in consequence, the gap wasn’t big enough, the child wasn’t diagnosed with a reading disability. Despite the fact that most youngsters can learn to read regardless of their IQ score, those with lower scores were often assumed to lack the “smarts” to read well.

An IQ test kept Sandra Chittenden’s daughter from getting the right help for years. The girl learned new words slowly and struggled to pronounce them correctly, mixing up similar-sounding words. In kindergarten she had no interest in letters and sounds, and she couldn’t easily see the similarities and differences across words on a page. Having a mild form of dyslexia herself and with an older son who is severely dyslexic, Chittenden, who is a special education advocate in Vermont, asked the school district to evaluate the girl for a reading disability.

The five-year-old was promptly given an IQ test. She posted an average overall score and a below-average score on a reading achievement test. But the gap between the two scores didn’t meet the cutoff of 15 points, so the girl was not given appropriate reading services in her school. The same thing happened when Chittenden requested another evaluation when her daughter was in first grade.

For the child, the results were wounding. During her first couple of years of elementary school “her nervous system was like a pressure cooker because she wasn’t being given appropriate help,” Chittenden said. “She held it together all day at school and then would explode.”

In third grade, the girl was diagnosed with a learning disability in math, and the school added a dyslexia diagnosis because of her continued struggles with both arithmetic and reading. But for years, Chittenden says, “I remember it being really frustrating knowing my child had dyslexia and not being able to get the right help.” As of this year, partly in response to parental concerns, Vermont is no longer using the discrepancy model to diagnose learning disabilities.

Researchers pointed out problems with the discrepancy model even before its use became prevalent in the U.S. Fletcher, an early critic, noted a methodological issue in the Isle of Wight studies: they did not exclude children with intellectual disabilities or brain injuries. Yet by some accounts there was an unusually large number of neurologically impaired subjects on the island at the time, resulting in a skewed sample.

It has also long been clear that IQ tests can be biased against Black or low-income students, as well as many others, because they contain language and content that is more familiar to white middle- and upper-income students. Researchers began to observe inequitable results in the late 1970s as American public schools began evaluating more children to comply with the mandates of the federal special education law, since renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

As a research assistant at the University of Minnesota, Mark Shinn said he saw how the discrepancy model disproportionately prevented children from low-income families, English learners and students of color from getting help. “You had all these kids in high-poverty schools with [below average] cognitive ability of 90 and 80, and the schools could throw up their hands and say, ‘They are too “slow” to benefit [from services],’” recalled Shinn, now a professor emeritus of school psychology at National Louis University in Chicago. Yet “it was well known that poor kids…earned low scores on cognitive tests largely because of a lack of opportunities and experiences.”

In the 1980s, educational psychologist Linda Siegel, now an emeritus professor at the University of British Columbia, began investigating some of these anecdotal suspicions. In an influential 1994 publication, she noted that the main distinction between children with a reading disability and those without was not their IQs, but the way their minds processed written words.

“The basic assumption that underlies decades of classification in research and educational practice regarding reading disabilities is becoming increasingly untenable,” she and her co-author wrote. In the same issue of the Journal of Educational Psychology, Fletcher and his colleagues observed that the “cognitive profiles” of poor readers who met the discrepancy definition and of those who didn’t were more similar than different. The key to diagnosing reading disabilities, they wrote, would be to instead measure “deficiencies in phonological awareness,” the ability to recognize and work with phonemes in spoken language.

Related: NAACP targets a new civil rights issue—reading

Since then, the scientific consensus against the discrepancy model has grown. One study found that regardless of their IQ, poor readers benefit from specialized reading instruction and support at statistically identical levels. Another used magnetic resonance imaging to show the same reduced brain-activation patterns in the left hemisphere (compared with those of typical readers) in weak school-age readers who were asked whether two written words rhymed—regardless of whether the weak readers met discrepancy criteria. Neuroscientist Fumiko Hoeft, who supervised the study at Stanford University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Brain Sciences Research, says it bolsters the idea that the discrepancy method makes an arbitrary distinction among different groups of poor readers. In fact, “dyslexia can occur in people of high, middle and low cognitive abilities,” noted Nadine Gaab, an associate professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

By the 2000s, ample scientific evidence indicated the arbitrariness of IQ’s use as a basis for a dyslexia diagnosis. And there were mounting concerns that the discrepancy model was fundamentally racist and classist: it disproportionately prevented low-income children and children of color from getting help with learning disabilities. In 2004, the federal government reversed course on its 1970s guidance, strongly recommending that states consider alternatives.

“I would…encourage this commission to drive a stake through the heart of this overreliance on the discrepancy model for determining the kinds of children that need services,” psychologist Wade Horn, then U.S. assistant secretary for children and families, told a panel of experts tasked with revising special education law in the early 2000s. “I’ve wondered for 25 years why it is that we continue to use it.”

But a 2018 study found that about one third of school psychologists were still using the discrepancy model to screen students for learning disabilities. And although most contemporary specialists concur that dyslexia is unrelated to intelligence, many of the most widely used definitions still refer to it as an “unexpected” disorder.

“These definitional issues are not trivial, because they drive research, they drive funding, they drive assessment, they drive everything,” said Julie Washington, a professor in the School of Education at the University of California, Irvine, whose research focuses on the intersection of language, literacy and poverty in African American children.

Even as more states and school districts move away from the discrepancy model, many researchers are concerned that they too often are replacing it with an equally problematic system. Often referred to as patterns of strengths and weaknesses or by Odegard as “discrepancy 2.0,” this method continues to rely heavily on cognitive tests and still calls for significant gaps between ability and performance for a student to qualify as having a learning disability. “Schools still want simple formulas and put way too much emphasis on the testing,” Fletcher said.

Twice in elementary school, Texas student Marcelo Ruiz, who lives just north of Houston, was denied a dyslexia diagnosis because of “discrepancy 2.0.” He had high cognitive scores, but evaluators said he did not show skill gaps in the areas he needed to qualify as dyslexic. School got harder and harder for Ruiz, and in high school he was still inverting letters and having trouble with reading. In the fall of 2022, his senior year, the teenager finally got a dyslexia diagnosis, but by then it was far too late to give him the help he had long craved. Because of his mediocre grades, Ruiz says, he had difficulty getting admitted into four-year colleges; he is currently at a community college and hoping to transfer. “Growing up, I felt stupid,” the 18-year-old says. “My grades kept going down, and I didn’t know what was wrong with me. It was really demotivating not knowing what I had and what you could do for it, not being able to get help.”

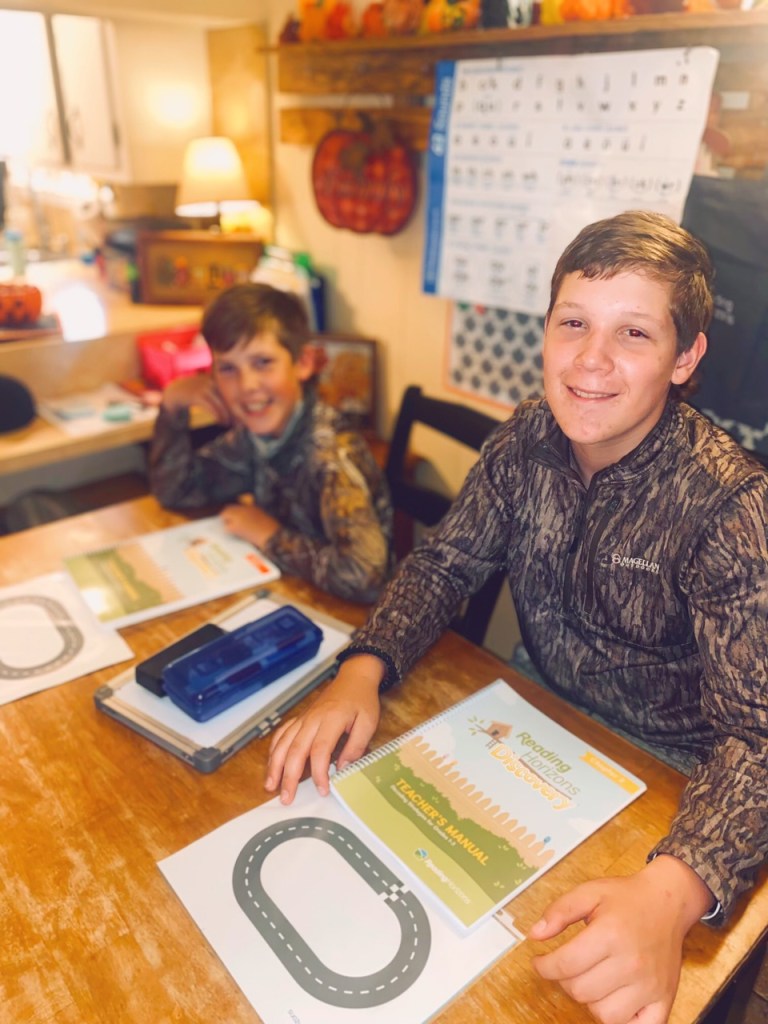

Texas mother Kodie Bates fought a similar battle on behalf of her sons—with the district reversing its opinion on whether the children had dyslexia. Both boys were diagnosed at the age of 7 with dyslexia using a method that still relied on testing and principles similar to the discrepancy model. However, the district did not provide any special education services. So in 2019, Bates began to push for an individualized education program, or IEP, that would delineate specific reading supports for her older son.

The district fought back, and a year ago, when her older son was 12, tried to reverse its own dyslexia diagnoses.

In a 34-page report provided by Bates and a special education advocate, the diagnostician for the Hooks Independent School District in northeastern Texas cited low cognitive scores in most areas for the older boy, arguing that the family’s decision to homeschool him may have impaired his cognitive abilities. “He does not have an unexpected (deficit)… Everything is in the below average range—to have dyslexia there has to be an unexpected (deficit) and I did not find one,” the diagnostician said, according to a transcript of a meeting held to discuss the report.”

“First they didn’t want to give him the services, and now they want to say that he is not even dyslexic—he’s just not smart,” Bates says. “It’s just not fair to take away a disability.” Last spring, an independent evaluator paid for by the district determined that her sons were, in fact, dyslexic as the district originally had found. Bates said she was grateful that the school is now offering services but has decided to keep homeschooling her sons with the support of online reading specialists.

“The boys are old enough now to be uncomfortable in such an environment and I don’t blame them one bit,” she said in an email.

They “are hesitant,” she added, “and let down.”

According to several researchers, a better—though hardly perfect—approach to assessing children for learning disabilities is “response to intervention,” or RTI. In this method, teachers intervene early with struggling readers and monitor how they respond to help, making a referral for special education services after what one research paper dubbed a “student’s failure to respond to treatment.”

Some states already require exclusive use of RTI, although it can be hard to implement because teachers have to be well trained in what interventions to administer and how to determine whether they are working. When teachers do make a referral for special education services, there’s often still a question of how—and whether—to make a learning disability determination.

For this reason, some experts in the field say they would like to see more no-cost or low-cost access to the kind of testing that qualified neuropsychologists do: assessing a child’s capacity for and speed at the many components that make up successful reading. (One bill pending in New York State would mandate that private health-care plans pay for neuropsychological exams focused on dyslexia.) The specifics can look quite different for a seven-year-old than for a high school student, Gaab explained. But generally, experts say testing should be used to gauge such skills as a child’s ability to recognize “sight words” (common words that often come up in reading), to sound out “nonsense” words that follow the rules of the English language but are not actual words, and to read under timed conditions and spell words correctly in their writing.

Related: Want your child to receive better reading help in public school? It might cost $7,500

It isn’t out of the question for school districts to do this type of testing on their own—and some of the best-resourced ones already do, or they contract with an outside neuropsychologist. But for most school psychologists, it would represent a departure from decades of training and practice focused on the administration of IQ and cognitive tests. The discrepancy model is “easier” because a child either meets the cutoff or doesn’t.

“It reminds me of leeching blood,” said Tiffany Hogan, a professor and director of the Speech & Language Literacy Lab at the MGH Institute of Health Professions in Boston. “They did that for a long time knowing it wasn’t the best way, but there was no replacement.”

Another largely overlooked reason for the continued prevalence of discrepancy-based testing may be that the families most hurt by it are the least powerful in terms of their influence over public school practice and policy. Many schools feel pressure, both covert and overt, to not identify children with dyslexia because there aren’t enough specialists or teachers trained to work with them. Families with money, power and privilege can negotiate with the district more effectively to meet their child’s needs or hire an advocate or lawyer to lobby on their behalf. If diagnosis and help still remain elusive, they can pay for private neuropsychological exams, which can cost thousands of dollars. They also can, and often do, circumvent the public system entirely by hiring private reading tutors or sending their children to private schools focused on reading remediation. (Often these schools also use the discrepancy model to determine whom to admit.) For all these reasons, as well as the discrepancy model’s bias favoring high IQ scores, dyslexia has long had a reputation as a “privileged” diagnosis.

The dyslexia advocacy community has in some states also been predominantly white and financially privileged, with low-income families and parents of color more likely to fear the stigma of a disability diagnosis. “Historically, we don’t talk about learning disabilities and mental health in the Black community because there’s a stigma and shame attached to it,” said Winifred Winston, a Baltimore mother who hosts the Black and Dyslexic podcast. “Enslaved people could not show any sign of weakness or perceived weakness. So we have a history of being ‘okay’…(even) when we are in fact not okay or do require assistance.”

Partly through the leadership of parents such as Winston, that’s changing as more families learn about reading disabilities and the extra support a diagnosis can bring.

Now 71 and 81, respectively, Jack Fletcher and Linda Siegel are still fighting to get children equal access to essential help in learning how to read. They are part of a broad-based effort seeking to strengthen access to general reading instruction for all so that fewer students get held back by learning disabilities or need intensive reading remediation. Many states are doing just that, with a growing number passing legislation promoting the “science of reading,” which emphasizes explicit and systematic instruction in phonics. Early screening for language challenges in the youngest grades is also key.

Still, Odegard said he regularly hears from families frustrated that their kids were disqualified from reading services for the same reason he was testing determined that they are not “smart” enough to be dyslexic. Odegard isn’t surprised that his own IQ was below average, given the correlation to socioeconomic status. His parents had modest-paying jobs in retail and neither had a college education.

The idea of distributing limited, extra help to students with high cognitive scores has deep roots in an American psyche “built off a mindset that somehow there are people who are chosen to move forward and some that are not,” Odegard added. It’s not dissimilar to “gifted” programs for children with high IQs or dual language programs that are only accessible to students with above average reading abilities. It’s the early, often irreversible, accrual of opportunity based on a limited, highly fallible notion of human potential.

Over the years, Odegard says, some colleagues and friends have remarked that, given his success, the experience must have made him stronger—a characterization he resents. “It wasn’t a gift,” he said. “I don’t see any of those challenges of having to stay up later and work five times harder as helpful.” Growing up, “I had a huge chip on my shoulder.”

On reflection, though, Odegard says there was perhaps one benefit to his early educational struggles. “If there was any gift I got from dyslexia, it was to have a lot of compassion and empathy,” he asserted, “because I could never hide in school that I couldn’t read and spell.”

Reporting on this piece was supported by the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University and the Russell Sage Visiting Journalist Fellowship.

This story about the discrepancy model was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

I am a 70yo white male, and I am dyslexic. When I was in 3rd grade (the second time), after hitting a teacher during a spelling test, my parents took me to see a large battery of specialists from social workers to psychiatrists. I was lucky because my father was in the US Army and the military paid for the evaluation. But, there wasn’t any help to be had. I was just given the diagnosis of being “handicapped in the ability to write”. My parents were also told that I had a very high IQ.

Because I graduated in 1972 and did not want to go to Vietnam as a “grunt”, I decided to go to college. Getting my BA in Psychology was one of the most difficult things I ever had to do. With such a degree and little prospects of getting a decent job, I struggled to get an M.Ed. in counseling.

From my earliest memories, I hated myself. On the one hand, I could not read or write, but on the other hand, I understood and gained knowledge faster than my classmates, due to my intellect. To deal with my internalized anger and self-hatred, I started drinking and doing drugs in high school (although I never did heavy drugs – I was too afraid of getting busted). In 1986, I sobered up and have been clean ever since. But I still have the anger inside.

Today, I am retired and volunteer with a ministry that works with the homeless. As I look at our clients (many of whom I consider my friends) I wonder how many of them, having turned to drugs and then to criminal activities to get the drugs to deal with their self-images, would not be living on the streets but having the kind of lives they want, had they been educated in a manner that would have been helpful. How much money that goes to incarceration and then dealing with them on the streets would have been better spent if they had gotten the help. Yet, the system does not change.

I’m hoping you reconsider the conclusion and general orientation of this article. I have enjoyed The Hechinger Report’s investigations for years, but this latest article is in my opinion, poorly directed. The dyslexia field has been ravaged over decades by swings of policy that have resulted in excluding students who would benefit from what we now know to be effective interventions – and I have already begun to hear of students being denied support in school that they very much need.

Based on what was shared, Dr. Odegard should have received intervention – and the student who missed by a few points as well.

But there is also extensive evidence that dyslexic students identified by a wide discrepancy between ability and reading achievement, can have their reading difficulties remediated by targeted intervention as well.

Don’t discriminate against these students. We should be helping all those who would benefit from the help rather than taking away from some to give to others.

Also, from our extensive practice with dyslexic students over the years, the IQ tests – although imperfect – can be extremely valuable. So many students (including those from under-represented groups and poor socio-economic backgrounds) may have their ability and intellectual strengths identified for the first time when they have an IQ test done. These students may have been failing at all the school basics – reading, writing, math – then suddenly it’s discovered there is an unexpectedly high IQ. It changes how the students see themselves, how parents see them, and how teachers see them, and ideally how their schools educate them.

I do know that many students may be beaten down, not understand the idea of IQ testing or be poor at expressing their ideas when they are tested so that test results don’t reflect their true ability – some recognition of these possibilities must also be made – and retest later if possible. But it is a terrible mistake write off discrepancy as a “disgraced method.” It is not.

Look at all the neuroscientific studies of dyslexia- including the pioneering studies involving fMRI. Almost all that we have learned in the last decade about the science of dyslexia comes from groups of dyslexic subjects who were identified by the discrepancy between a measure of their intelliegence and single word or nonsense word reading.

Let’s also learn from the individual cases that get excluded and plan our education on individuals rather than consensus definitions.

We should be thinking more about how to help all students rather than to take away resources from some to give to others.

In my fourteen years conducting neuropsychological testing, I have seen the discrepancy model used to disqualify numerous students struggling with reading from special education services. The model cuts like a double-edge sword. Both children who have average IQs and struggle with reading, and children with above average IQs and mediocre reading skills, often do not show “enough” discrepancy to qualify for services.

Undeniably, the discrepancy model punishes both types of students. However, the impact on economically disadvantaged students is not buffered by outside resources, as it is for wealthier students.

I believe that Response to Intervention (RTI) is not the solution. This model requires intensive teacher training and time consuming reviews, reconsideration, and reevaluation. Given funding and staffing shortages that most schools face, using the RTI model means that children will flounder for longer while not obtaining needed supports.

Instead, we should: 1) Spend our resources on retraining teachers to utilize the “science of reading” paradigm to help all students develop reading skills; 2) Implement universal dyslexia screening to identify at-risk children early; 3) Provide intensive and evidence-based instruction to all children with identified reading difficulties, regardless of IQ. We need to change how all children are taught to read and how dyslexia is diagnosed.

It was nice to see this issue getting attention. However, the focus of the story suffers from the same problem it aims to address: that the field of learning differences is very broad and encompasses multiple aspects of human brain functioning – cognitive, sensory, executive functioning, emotional management – Not Just Dyslexia!

I am a 77 year old retired Clinical Social Worker (MSSW, PhD) who spent the second half of his 40+ year career specializing in the diagnosis and treatment/remediation of learning disorders in children and adults. My focus was on the range of learning differences: Language Processing Disorders (Dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalcula, dyspraxia), ADHD, Sensory Processing Processing Disorders, Anxiety Disorders, Mood Disorders, Autism Spectrum Disorders, Executive Functioning Disorders.

This story aims to address the “discrepancy model”, meanwhile, there have been several additional methods of assessing learning disorders used by our Nation’s Schools that have also fallen woefully short of fully identifying or remediating student learning problems. The impression is created of a singular learning problem improperly addressed by a singular solution, as if it stands alone!!!

Truthfully, I am horrified that a publication of the stature of Scientific American would publish such a narrowly focused and short-sighted story!

Not only I, but many of my colleagues were well aware of the poor job many of our schools did in assessing and remediating learning problems (despite the long existence of more effective methods) way back in the 1970’s!

This makes me wonder about the thoroughness of the scope of other Scientific American stories!

As an elementary reading and math teacher, I have worked in the discrepancy world. That method of identifying and providing help to the child, guarantees that the child will not receive the specialized instruction until it is too late.

I have also tutored kindergartners and first graders, sending progressing children back to the classroom and giving more time and specialized instruction to the children who needed more help. The Response to Intervention model worked quite well for most of the young children. Most caught up to the class and continued to learn.

The Discrepancy Model is like parking the ambulance at the bottom of a cliff. When the child arrives for help it is too late.