TAOS, N.M. — Standing in front of 240 freshmen and 80 fellow seniors in her school’s gymnasium, a slight 17-year-old with her hair in pigtail braids took a long shuddering breath.

Her audience was still. The girl had just revealed that she’d spent most of her middle-school years feeling suicidal, had been hospitalized for her own protection and spent two years in therapy before finally telling her mother the cause of her deep depression and thoughts of self harm: She’d been raped by a man she knew.

After two beats that felt like an eternity, the room exploded into supportive applause. The girl’s face crumpled as friends rushed to her side. With the buoying effect of the hugs from her friends and all the cheering, she regained her composure.

“I felt like it was my fault,” she said of the rape. “I felt like I provoked it.” She said she’d learned through therapy and open communication with her parents that rape is never the victim’s fault and that thinking about suicide is not a sign of weakness.

“You can get through the worst thing and come back from it,” the girl with the braids told the assembled freshmen, who sat in the orange and black bleachers facing a group of seniors seated in rows of chairs on the basketball court. “I’m alive. I don’t want to die anymore. I’m here. I’m OK. I’m living to the best of my abilities.”

It was the third day of Taos High School’s EQ, or emotional intelligence, retreat. Led by senior volunteers, the retreat has become a spirit week tradition in this rural New Mexico county over the past eight years. The retreat, timed to coincide with a week full of themed dress-up days and sporting events aimed at raising school pride, serves as a way to welcome freshmen to campus and assure them they are not alone in facing the challenge of their high school years.

The idea that schools might be responsible for addressing the mental and emotional health of their students has become mainstream over the past decade, said Jessica Hoffmann, a research scientist and the director of high school initiatives at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence. But it’s increasingly becoming a responsibility that school leaders say they feel they must shoulder if they are going to help students achieve academic success. Fourteen states, including Arkansas, Nevada and Tennessee, now have social-emotional learning goals for K-12 students, according to the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, a national nonprofit focused on integrating social emotional learning into American school curricula. New Mexico is not one of them.

“It’s a culture shift to recognize that humans are emotional beings and emotions can be harnessed and channeled to improve academic performance and improve relationships and improve decision making,” Hoffman said.

Educators, policymakers and students from across the country seem to be making that shift. Emotional and mental health, school climate and school culture were priority issues for all three groups, according to a recent study by Child Trends, a research organization focused on issues affecting children. Students mentioned school climate as an important part of their mental and emotional health about twice as often as teachers and policymakers, who mentioned family, community and other outside issues more often than students did.

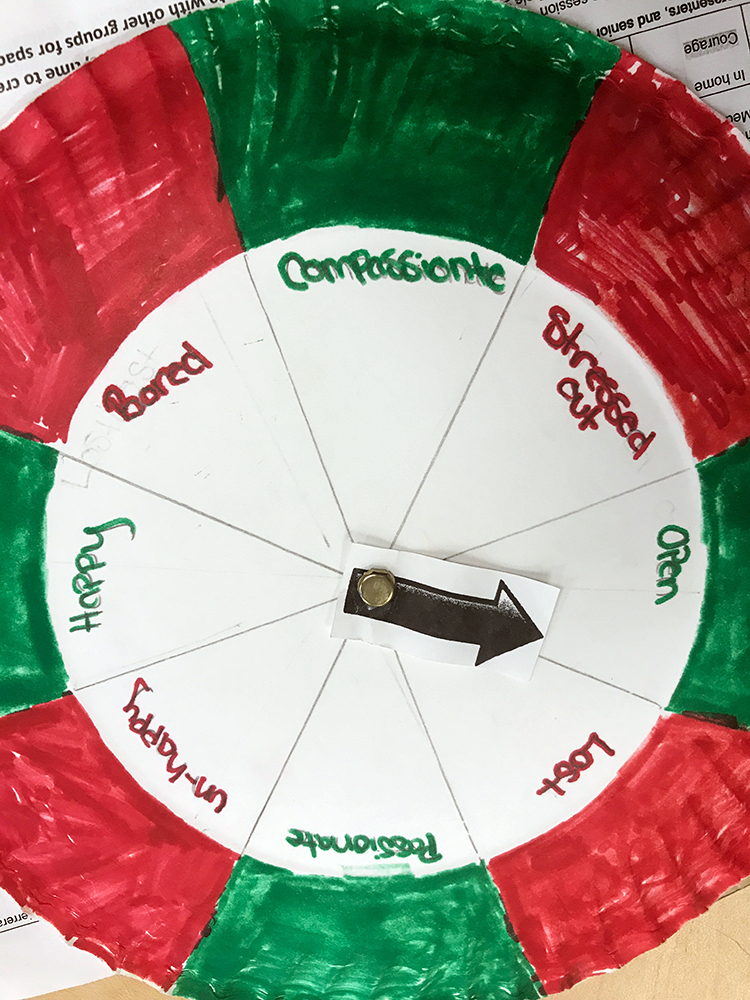

High school, it seems, is an uncomfortable place for a lot of students. Asked in a 2015 survey to describe how they felt in school, the words high school students used most frequently were “tired,” “stressed,” and “bored.” In fact, about 75 percent of the words students chose to describe how they felt at school were negative. The survey, which was administered to 22,000 high school students from around the country by researchers at Yale’s Center for Emotional Intelligence, also found that students who reported their peers had been mean or cruel expressed greater levels of loneliness, fear and hopelessness.

Related: NYC’s bold gamble: Spend big on students’ social and emotional needs to get academic gains

The EQ Retreat is Taos’ answer to the problem of too many students spending their school days feeling down. Teachers and community members lead sessions on dealing with grief through meditation, teach improv skills to help students learn to stay in the moment and walk students through activities meant to demonstrate how much they have in common. But the 17- and 18-year-old seniors occupy the starring role, as far as the freshmen are concerned. They lead ice-breaker games, run an art project, share their own stories of struggle, encourage the freshmen to come to them with problems and make sure they learn the name of every younger student in their group.

Sasha Kushner, a freshman with bright red hair, said she’d been a little worried about spending so much time with seniors, who might judge her or be mean to her. “But after a while, they were awesome and I got really close to them,” Sasha said. “We kind of respect each other.”

Several seniors pointed out that though they were older than the freshmen, it was only by a few years. They said they could still relate to how it feels to start at a new school, meet lots of new people and try to figure out who you are in the midst of all that change.

“We care for each other and we’ll get through it together,” said senior Angel Martinez. Adults may have gone through similar things in the past, she added, “but times have changed from then to now.”

“I wanted the freshmen to feel safe,” said Manuel Baca, another senior who shared a story of struggle. “I was just hoping to open up everything I had inside and share as much as I could, while at the same time as showing the freshmen that it’s OK to share.”

Opening up can be hard though, and Baca, who spoke to freshmen about some tough times in his family when he was younger, admitted that his voice was breaking at the end. “It was hard to hold it in,” he said.

Was he worried about crying in front of his peers? Not really, Baca said. “I feel like that’s actually old-school type of emotion. I feel like the new society we’re kind of running is more open to each other. It’s less sexist and we’re all on the same team.”

Having a student like Baca, who throws discus for Taos’ record-holding track team, act as a role model and get up in front of a few hundred kids to share his feelings is an event many school leaders would hardly dare hope for.

For the most part though, the seniors come to it naturally, said Ned Dougherty, the teacher-leader of the EQ retreat. With his glasses and mussed dark hair, Dougherty looks a little bit like a grown-up Harry Potter. He believes firmly that his students’ best path forward is to depend on each other. “Peer-led social-emotional learning is the answer,” he said.

His role as a teacher, he added, is to give students time and space at school to both process their emotions and learn how to handle them.

“Our kids are tired of education,” said Dougherty, who teaches history. “Our kids don’t think adults see them as having a place in the world. They haven’t seen much outside of rural America. On the one hand, you can see them as fragile and vulnerable. On the other hand, they’re hardened to life.”

Known to outsiders as a resort town and artists’ retreat, Taos County is home to a mostly low-income population; 82.9 percent of the school district’s students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a federal measure of poverty. The high school’s top-notch sports program and its Advanced Placement courses help a few students head off to prestigious out-of-state colleges every year. Yet, as in many New Mexico schools, few prove proficient on state tests of reading (34 percent) or math (10 percent). School is even harder for students dealing with hunger, addiction or mental illness at home.

Not everyone at the school thinks holding a three-day retreat that highlights teenagers’ emotions is the best idea, as Dougherty himself acknowledges. Some worry that the retreat exposes issues, fails to address them, then leaves them to fester, Dougherty said.

Even some of the adults who are involved in running the retreat and profess great respect for its leader have concerns about some of the methods. Victoria “Amani” Carroccio, a certified school counselor who works at Taos High School as a wellness coach, thinks teaching student skills to deal with trauma, grief and loss is a wonderful idea. But she thinks that traumatized teens should not be sharing their stories in a room full of people.

“Trauma is not healed by retelling the story,” Carroccio said a few weeks after the retreat. “There is something about breaking the silence, don’t get me wrong. If I checked in with them now, my guess is they would be re-traumatized.”

Sexual assault, suicide and self-harm were three of the more traumatic topics raised by seniors, either in front of the entire freshman class at the morning session in the gym or in smaller group sessions with their assigned freshmen. Suicide came up more frequently at this year’s retreat than it has in years past, some said, which might be because it’s increasingly on young people’s minds.

Teens nationally were more likely to report feeling persistently sad and hopeless in 2017 than they had for 10 years, according to the latest Youth Risk Behavior Survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And while most risk-taking behaviors — from using drugs to having sex — have been on the decline since the mid-90s, the rate of suicide-related behaviors has risen in the last decade. In 2017, 17.2 percent of the 14,856 Youth Risk Behavior Survey respondents reported that they had “seriously considered suicide” in the past 12 months. The rate of teen suicide has also risen since 2007.

Given that the suicide of one young person can sometimes spur a second youth suicide, educators are often reluctant to have the subject brought up in school. However, the research shows that talking about suicide at school can actually help prevent additional deaths if the topic is not sensationalized and help is offered. To this end, suicide screenings, which ask students a few basic questions about whether they’ve thought about harming themselves or others, are recommended by the American School Counselor Association, according to its assistant director, Eric Sparks.

And hearing from a fellow student who has been suicidal but found a way through those feelings can be a great way to help teens who are suffering, said Jonathan Singer, a member of the board of directors of the American Association of Suicidology and an associate professor of social work at Loyola University in Chicago.

“If they say, ‘Hey high school sucks, it’s pretty miserable, everybody thinks about killing themselves at some point. I was pretty close…’ and if they start talking about the means in detail, that’s not going to be a very protective conversation,” Singer said.

Dougherty and the other teachers who helped seniors prepare for the Taos High School retreat urged seniors to think beyond sharing the details of their stories by asking them to consider what wisdom they could offer the freshmen.

“Anyone could get up and tell them a story, but what do they need from you?” Dougherty said they asked seniors. The answer: “They need a way out of it, they need an action plan, they need hope.”

Related: Almost two decades after Columbine, how to prevent school shootings still vexes security experts

Best practices before having students share personal stories in a public forum would include asking staff members to pre-screen those stories, according to Sparks, of the counselor association. Vetting stories could help staff prepare for potential effects on students, Sparks said.

The stories in Taos have never been vetted. Dougherty said he was receptive to new ideas about how to run the stories section of the event, but he also pointed out that the stories provide the clearest example of positive impact on the freshmen. Students remember these uncensored stories for years. The seniors who led the retreat this year could recall exact details of stories they heard from the seniors at their freshman retreat four years prior. Several said they were moved to lead this year because of the power of their freshman experience.

At the 2018 retreat, both the students who told the stories and many of those who heard them reported feeling empowered and reassured, even as they admitted that much of the content was sad or disturbing.

Freshman Isaiah Vigil said he learned that “it’s not the end of the world when something that could seem horrible happens. Life will go on. You’ll endure. And you’ll get through it eventually.”

Isaiah and other students said opening up about family difficulties, sexual assault and suicidal feelings is a way to care for each other and ensure that nobody feels totally alone.

“There’s not enough discussion of hardship and trauma at high schools,” said senior Leah Epstein. “To ignore it and pretend it doesn’t exist doesn’t help at all.”

The girl with the braids, taking a break from lunch a few hours after telling her story, agreed. “I expect to get judged a little bit and I’m OK with that,” she said. “It’s a relief to get it off my chest. I keep on having people come up to me and hug me and tell me they’re there for me.”

Finally opening up to her mother had helped more than almost anything during her journey through hardship, the girl said. She now believes that being open with problems is the best way to face them. “Any kind of backlash, good or bad, I don’t regret it,” she said. Nearly two months later, she said by email that she still felt better for having shared her story.

Dougherty and other teachers followed up informally with the girl with the braids and other students who shared tough stories to see if they needed additional mental health services. Seniors were also coached on when to bring concerns they heard from freshmen to the attention of adults.

Of course, not every high school student is dealing with extreme hardship and trauma. But even the realization that they are lucky to live relatively privileged lives isn’t always enough to blunt the often stressful effect of teenagers’ more typical anxieties about fitting in, making good grades and living up to family expectations. At Taos, a wide variety of conversations over the course of the three days made room for these students too.

“The advice I got that was really important was: ‘Be yourself,’” said Joshua Gonzales, a freshman. “You don’t have to change for anyone. Whether it’s your family or you’re in a relationship or your friends are pressuring you, don’t change. You are your own person.”

Helping students go beyond talking about such principles and actually being able to live by them will probably take longer than three days, Yale’s Hoffmann said. The two national programs she oversees — RULER and InspirED — are meant to educate teachers and students about how to make emotional skills part of their daily life at school.

“We try to show them that emotions are coming in the door whether you want them or not,” Hoffmann said. “There’s still in our society in many places an expectation that you can leave your emotions at the door and be a robot and it’s simply not true. Not only is that not true, but your emotions can actually enhance your learning and the kind of innovative things you do in science or math or art.”

Related: Rural schools find an online resource to fill gaps in mental health services

Emotional intelligence as a concept made its debut in Germany in the mid-1960s and was popularized in the mid-90s by science journalist Daniel Goleman’s book on the topic. Goleman, in turn, based his book on the research of John Mayer, a psychology professor at the University of New Hampshire, and Peter Salovey, now the president of Yale University. In 1990, Salovey and Mayer published a paper outlining the idea that humans can improve their mental health and interpersonal relationships if they learn to recognize, understand, label, express and regulate their emotions. Several additional papers followed which, together, now provide the foundation for the Yale programs on social-emotional learning in high schools.

Taos High principal Robert V. Trujillo hopes that the school’s relatively new advisory period — a sort of extended homeroom— could prove the perfect vehicle for expanding the school’s emotional intelligence curriculum all year, to all grade levels.

“Pulling days and extracting days from academics can be very challenging,” Trujillo said. “But one doesn’t go without the other. If kids aren’t ready to learn because of the difficult emotional state they’re in, then it doesn’t help anyway, no matter how many days they’re in class.”

This year’s seniors have been working with Dougherty to create a program that runs throughout the year. They have already had their first follow-up meetings with freshmen. Now they want to pass on what they’ve learned about healthy ways to deal with emotion to middle school students as well.

”I wanted the freshmen to feel safe.”

In 2016, in honor of their work to improve student wellbeing, Taos High School received a small monetary award from Yale and Facebook’s InspirED initiative. But the program’s origins and its current iteration are pretty homegrown — imagined first by students and nurtured over eight years by a series of overlapping teachers and community members. Dougherty thinks the retreat could likely be replicated elsewhere, in part because the on-campus event run largely by student volunteers costs so little.

The primary expenditure, teachers and administrators say, is time. For nearly a decade now, EQ retreat leaders have been granted three days to focus student attention, not on math and reading, but on providing all students with a sense of belonging, the knowledge that someone at school cares and concrete skills to deal with the roller coaster of emotions endemic to being a teenager.

Certainly, kids say, the program hasn’t fixed everything. With little prompting, a group of seniors started listing where each clique sat at lunch: The art kids go to Hensley’s class for lunch, the cool kids are in the lobby, the nerds are in a classroom, jocks have to eat with their coaches, the band kids hang out outside band room, the 4-H kids are outside at the tables, the drama kids are by the theater… The list goes on.

“I just know these people a little,” senior Tyler MacHardy admitted as he looked around a circle of fellow-retreat leaders. “The effect on the seniors is maybe even greater than the effect on the freshmen,” he said, “just from being put in that situation where you’re forced to collaborate.”

It’s fine that the school isn’t a perfectly serene haven all the time, said Francis Hahn, an English teacher and Taos High alum who has assisted with the retreat since its inception.

“Public high school is a place for drama. If there weren’t any drama, it would be a somewhat diminished place,” he said. “One of the important things students do in high school is learn how to negotiate conflicts in ways that are appropriate.”

“Peer-led social-emotional learning is the answer.”

Hahn, who has worked at Taos High for 13 years, said he’s witnessed a change in the school climate since the retreat started. (He is careful to add that a “No cell phone,” policy was established around the same time and that may have also contributed to having calmer halls and fewer fights.)

“For me, it’s not about seeing the tangible change in the school,” Hahn said. “It’s about the hope that we’re planting a seed that will flower and fruit in their later lives.”

Early on the third day of the 2018 retreat, not long after the girl with the braids finished telling her story, a group of seniors and freshmen sat in a classroom upstairs. The teacher asked that each student share his or her feelings with just one word.

“Tired.” “Fine.” “Sad.” “Empathetic.” “Detached.” “Foggy.” “Fragile.” One by one the kids described their emotions. A slight girl with bright red hair came in crying. That girl, Sasha, who later said she’d started the week nervous that the seniors would be mean to her, had been in the bathroom crying before the class started and seemed to be trying to focus on the room, but was too distraught. She took a seat for a second, lost her composure and left again. A senior followed her to offer comfort.

Hours later, Sasha was smiling, happy, eager to return to the spirit week volleyball game being played by — get this — boys! The morning had been hard, she said, but eye-opening too.

“Even when it seems like the darkest times, there’s always hope,” Sasha said. “You can always find a way out.”

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or the Crisis Text Line — text TALK to 741741 — are free, 24-hour services that can provide support, information and resources.

This story about social-emotional learning was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

At The Hechinger Report, we publish thoughtful letters from readers that contribute to the ongoing discussion about the education topics we cover. Please read our guidelines for more information. We will not consider letters that do not contain a full name and valid email address. You may submit news tips or ideas here without a full name, but not letters.

By submitting your name, you grant us permission to publish it with your letter. We will never publish your email address. You must fill out all fields to submit a letter.