Last year, Arizona became the first state in the nation to offer universal school choice for all families.

State leaders promised families roughly $7,000 a year to spend on private schools and other nonpublic education options, dangling the opportunity for parents to pull their kids out of what some conservatives called “failing government schools.”

But now, some private schools across the state are hiking their tuition by thousands of dollars. That risks pricing the students that lawmakers said they intended to serve out of private schools, in some cases limiting those options to wealthier families and those who already attended private institutions.

Critics of Arizona’s empowerment scholarship accounts, or ESAs, cite the tuition increases as evidence of what they’ve warned about for years: Universal school choice, rather than giving students living in poverty an opportunity to attend higher-quality schools, would largely serve as a subsidy for the affluent.

“The average amount of tuition is going to be more than the actual voucher, not to mention transportation and uniform costs,” said Nik Nartowicz, state policy counsel for Americans United for Separation of Church and State, a legal advocacy group. “This doesn’t help low-income families.”

A Hechinger Report analysis of dozens of private school websites revealed that, among 55 that posted their tuition rates, nearly all raised their prices since 2022. Some schools made modest increases, often in line with or below the overall inflation rate last year of around 6 percent. But at nearly half of the schools, tuition increased in at least some grades by 10 percent or more. In five of those cases, schools hiked tuition by more than 20 percent – much higher than even the steep inflation that hit the Phoenix metro area and well beyond what an ESA could cover.

Nationally, a dozen other states now offer ESAs, also known as education savings accounts, that incentivize parents to withdraw their kids from the public K-12 system. Another 14 states offer vouchers, which allow families to direct most or all of their students’ per pupil funding to a private school. As the programs grow in number, they offer a test of subsidized school choice — a longtime goal of the political right — and its effectiveness in serving kids from all backgrounds.

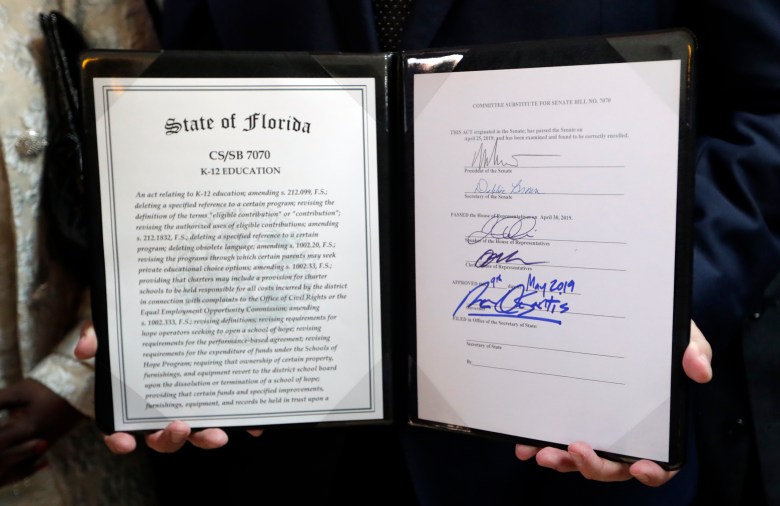

Related: Florida just expanded vouchers — again. What does that really mean?

As of September, nearly 62,000 students in Arizona have received an ESA — more than twice the number that received the aid in the same month last year. Participating students receive 90 percent of what the state would spend to educate them at a public school; children with disabilities can access much higher funding. Recent state data pegs the median ESA award at just under $7,200. Families can spend their ESAs on almost any education-related expenses, such as private school tuition, tutoring and homeschool supplies.

Before Arizona expanded eligibility for ESAs last year, proponents of the program argued the median award would cover median tuition at private elementary schools and about three quarters of the median rate at private high schools. Now, the recent rise in tuition may price more Arizona families out of the nation’s most expansive experiment in school choice.

For example, the cost of enrollment for seventh and eighth graders at Arrowhead Montessori, in Peoria, soared to $15,000, an increase of $4,200. In Mesa, tuition at Redeemer Christian School rose by nearly a quarter across most grades; families of high schoolers now pay $12,979, approximately $2,500 higher than the year prior. Similarly, at Desert Garden Montessori, in Phoenix, middle and high school tuition is now $16,000, nearly 24 percent higher than last year’s tuition rate of $12,950. And Saint Theresa Catholic School, also in Phoenix, reserved its biggest price hike – of about $1,800, or nearly 15 percent – for non-Catholic students in the elementary grades. Tuition for those students is now more than $14,000.

The Arrowhead, Desert Garden, Valley Christian and Redeemer Christian schools did not respond to requests for comment. ESA proponents, meanwhile, dismissed any tuition inflation as early growing pains.

Lisa Snell, a senior fellow of education at Stand Together Trust, a libertarian think tank, said that over time more private schools and educational providers will open in the state, creating greater market competition and pushing down costs. Already, Arizona has registered more than 4,000 vendors for ESAs — including retailers, tutors and even traditional school districts — a jump of 35 percent over last year.

“There’s obviously more risk with experimentation, but the only way to improve quality is to allow people to experiment,” Snell said. “We’re at the very early days.”

Related: COLUMN: Conservatives are embracing new alternative school models. Will the public?

ESAs gained prominence with Arizona’s passage of the nation’s first such program in 2011.

The state initially reserved participation to children with disabilities, but lawmakers later expanded the program to other populations, including children of active-duty military members and those attending a school that earned a D or F on state accountability report cards. Originally, most eligible students had to attend a public school for the first 100 days of the prior school year before applying for an ESA.

Then, in 2022, state leaders expanded eligibility to all K-12 students and removed the requirement of initial public school attendance. The Arizona Department of Education, which administers the program, estimated nearly half of students with an ESA have never attended public school — suggesting the state is sending millions of dollars to families who’d previously covered private school tuition out of their own pockets.

For some families, including those already enrolled in private school, the tuition hikes have caused sticker shock.

Pam Lang previously received an ESA for her son, who has autism, to attend a private school for students with disabilities. A real estate agent in the Phoenix area, she confirmed tuition at his program rose nearly $4,000. She said families received no prior notice of the increase, which showed up in an invoice before the start of a new academic year.

“Parents are faced with the possibility of having to drop other things they use ESAs for, like tutors — an expense that also increased for my son,” Lang said.

Meanwhile, some private schools encourage currently enrolled families to secure an ESA to cover the higher tuition rates, according to Beth Lewis, executive director of Save Our School Arizona, a group that advocates for public education.

“It makes complete economic sense,” Lewis said. “If a family was already able to pay $11,000, what’s stopping the school from increasing tuition by the average ESA?”

Advocates of the program, however, argued families of varying income levels will make room in their budget for private schools.

Matt Ladner, a fellow with the nonprofit group EdChoice, said low-income parents might find second or third jobs to afford tuition for their kids. And, he added, even children whose families pay for private school on their own dime deserve some portion of state funding for education.

“Their parents pay taxes too,” Ladner said. “Everyone pays into the system, and everyone with a child should be entitled to an equitable share. We publicly fund education for all kids.”

Related: School choice had a big moment in the pandemic. Is it what parents want in the long term?

Of the 13 states with some version of ESA legislation, five — Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, Utah and West Virginia — followed Arizona’s lead in granting eligibility to 100 percent of students, regardless of income level. The Grand Canyon State, though, stands apart in almost hands-off approach to the private school market.

Existing state codes set no requirements for the accreditation, approval, licensing or registration of private schools in Arizona. No public agency tracks the creation of new private schools in the state or what they charge for tuition. The state departments of education and treasury did not respond to repeated public records requests for vendor data on how families have spent their ESA awards.

“It’s a black box by design,” said Lewis.

“The average amount of tuition is going to be more than the actual voucher, not to mention transportation and uniform costs. This doesn’t help low-income families.”

Nik Nartowicz, state policy counsel for Americans United for Separation of Church and State, a legal advocacy group

In contrast, Iowa requires parents to use their ESA at an accredited nonpublic school — a requirement that Snell, of the Stand Together Trust, described as limiting and rigid.

She and other fans of Arizona’s law said its looser structure will open the door to many more choices for families. One option: microschools, where families bring their children together in smaller learning communities, with or without a licensed teacher.

“It’s kind of a great thing about demand-driven systems,” Ladner said. “We don’t know what families will value and what directions they will take things.”

He also pointed to a new report from the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, showing that increases in private school tuition over the last 10 years were smaller in states that passed school choice policies than in those that didn’t.

Dan Hungerman, an economics professor at the University of Notre Dame who has studied the impact of vouchers on private school finances, noted that the Heritage report’s main finding lacked the common elements of rigorous academic research: statistical significance and standard error.

Hungerman’s own research, conducted in partnership with an economist at the U.S. Census Bureau, found that voucher programs significantly boost the bottom line of churches that operate private schools and likely prevent church closures and mergers.

That concerns Joshua Cowen, a professor of education policy at Michigan State University. He said that high-tuition private schools were already out of reach for most students and will remain so, regardless of ESA programs. More distressing, Cowen argued, were the public campaigns — including one from a foundation backed by former U.S. education secretary Betsy Devos — aimed directly at saving Catholic education through school choice.

“Vouchers are at least partly about bailing out financially distressed church schools,” Cowen said. “Once school vouchers come to town, taxpayers become the dominant source of revenue for churches.”

In Chandler, the Seton Catholic high school sets two tuition rates: A $18,775 general rate for students enrolling in the 2023-24 academic year, and a discounted rate of $14,100 for Catholic students. The college prep academy requires families to secure verification from their parish to receive the discount.

“As a Catholic school, we work with people of all faiths, but our ministry exists to serve the Catholic church,” said Victor Serna, the school’s principal.

“If you want this to be a shining example for the country, you gotta change some things. Because right now, we’re on the fast track to disaster.”

Beth Lewis, executive director, Save our Schools Arizona

Nartowicz, with Americans United for Separation of Church and State, said he suspects that as more states pass ESA legislation like Arizona’s, the number of church-based schools offering discounts based on religion will also increase, allowing the use of public funds, in effect, to advantage those with particular religious views.

“We’ve never really encountered this before,” Nartowicz said.

Earlier this year, the Arizona department of education projected the expansion of ESAs would cost the state about $900 million — well above an original estimate of just $65 million. The ballooning price tag prompted Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs to call on lawmakers to repeal the program’s universal eligibility. Republicans in control of both legislative chambers rejected the idea.

ESA critics had hoped a bipartisan deal to create an oversight committee would lead to reforms of the program. But earlier this month, the committee ended its work with no proposed changes.

Lewis, with Save our Schools Arizona, had previously said that the deal indicates even some Republicans may be worried about the financial impact of school-choice-for-all.

“If you want this to be a shining example for the country, you gotta change some things,” she said. “Because right now, we’re on the fast track to disaster.”

But the state speaker of the House, Ben Toma, a Republican who chaired the ESA oversight committee, seemed to buck expectations that the program would significantly change soon.

“School choice is here to stay,” he wrote on social media.

Amanda Chen contributed reporting.

This story about Arizona school choice was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

The article is loaded with factoids and statistics that seem to be selected to torpedo school choice in Arizona. Charts showing how tuition at a broad range of participating private schools, and also per capital funding in public schools would tell more of the story, and be far more credible.

Private schools are likely to require capital investments for expansion that public school is do not. Would the cost of constructing a new public school be amortized and justify an increase in the annual state allocation per student, or would it cut deeply into the annual funding for teacher’s salaries, and books or other resources?

This expansive argument against school choice excludes information.and avoids a format that would clarify the issue in favor of a presentation with select, isolated factoids in terms that vary to much to be digested, compared, and analyzed.

I would prefer that private schools cap their tuition, but our local parochial schools’ set tuition high enough so that discounts and scholarships can be provided to the needy.

If an anticipated influx of low-income families need $3000 of their own funds to cover recent tuition rates of $10,000,but would make perfect sense to raise tuition to $15,000.

Those who’d been out of pocket for $10,000 a year would apply the $7000 grant and pay $2000 less, per child, per year.

That $5000 increase per student could go to scholarships that combined with the $7000 grant to pay $12,000 for each low income student.

The additional $3000 could be waived, although many low income families could afford to pay that $3000 with their earnings. And if possible, they should earn and pay that amount; public education fails to some extent because parents don’t directly pay anything for it. Even if they only pay a minor fraction of the costs, they’ll be highly motivated to compel their kids to do homework, behave and succeed . . . . or lose their scholarships and be returned to a public school.

My extemporaneous exploration of what’s likely to happen is arguably more clear and credible than the professional report in the article.

Governor DeSantis did this in Florida. When he’s giving this money to the rich people to help subsidize their school and they’re also allowed to spend it on big screen TVs and trips to like Disney World and stuff because he says those kids need more stimulation. But he’s taking money away from the public schools and why don’t those kids need more stimulation? It just makes me sick.