As the coronavirus pandemic ravaged communities and shuttered schools, many educators and parents worried about kindergarteners who were learning online. That concern now appears well-founded as we’re starting to see evidence that remote school and socially distanced instruction were profoundly detrimental to their reading development.

Children in kindergarten when the pandemic broke out in the spring of 2020 are now roughly eight years old and in third grade this 2022-23 school year. A new report by the nonprofit educational assessment maker NWEA documents that third graders are currently suffering the largest pandemic-related learning losses in reading, compared to older students in grades four to eight, and not readily recovering.

Learning to read well in elementary school matters. After children learn to read, they read to learn. Poor reading ability in third grade can hobble their future academic achievement. It also matters to society as a whole. Students who fall behind at school are more likely to be arrested, incarcerated and become teen mothers. A separate December 2022 analysis calculated that if recent academic losses from the pandemic were to become permanent, it would add up to $900 billion in lower lifetime earnings for the 48 million students in public schools.

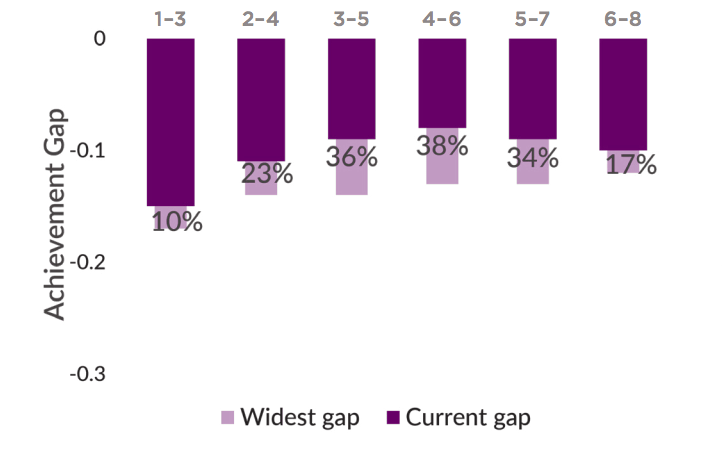

That’s why NWEA’s findings for third graders are alarming. The results emerged from an analysis of fall 2022 test scores of seven million elementary and middle school children across the nation, in which the reading abilities of third graders remained far behind what children used to be able to do in third grade before the pandemic. The differences between pre- and post-pandemic reading levels are smaller in older grades. While it’s good news that third graders are learning at a typical pace again and no longer falling further behind, they are also not gaining much extra ground. Their learning recovery is the smallest among students in grades three through eight. (See the purple reading graphic below.)

Third graders in 2022 are the furthest behind in reading, as depicted by the bar on the far left. So far they’ve recovered only 10 percent of their pandemic learning losses, which were at their greatest in the spring of 2021. Older grades are making better progress in catching up.

Karyn Lewis, a researcher at NWEA who led this analysis of test scores, said that current third graders are “a group that we really need to pay a lot of attention to” because the pandemic disrupted their kindergarten and first grade years when they were supposed to learn foundational reading skills.

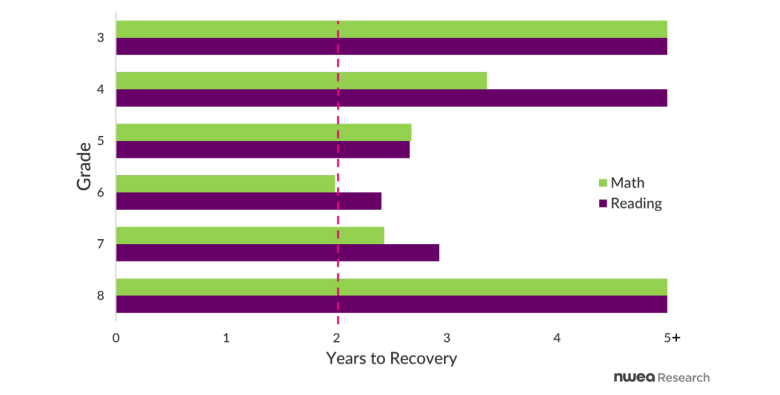

Slightly older students in fifth, sixth and seventh grades, who were in second grade and above when the pandemic hit, are making much better progress in reading. If their current pace of learning continues, they’ll be on track to recover in two or three years, Lewis calculated. By contrast, it’s unclear when, if ever, current third graders will even catch up to pre-pandemic norms in reading. Lewis said there is a “long road to go” and that she estimates it will be “five plus years” for these third graders to catch up. That would be after eighth grade for this class of children. (See recovery graphic below.)

Estimated years to reach recovery by subject and grade

It’s worth noting that pre-pandemic reading levels weren’t spectacular and had been deteriorating; most children were not proficient in reading for their grade level, as measured by a national yardstick. So, it’s an estimated “long road” to return to a rather low level of achievement that was already a subject of consternation and hand-wringing.

The NWEA research brief, Progress towards pandemic recovery: Continued signs of rebounding achievement at the start of the 2022-23 school year, was released on Dec. 6, 2022. It analyzes scores on its Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) assessments that are purchased by more than 22,000 schools to measure student progress in both reading and math twice a year, in the fall and the spring. These are in addition to mandatory state assessments taken by students each spring.

This latest NWEA report describes how student achievement deteriorated in 2020 and hit a bottom in the spring of 2021, after which student learning stabilized – a sign that students were once again learning at a typical pace as schools reopened.

Though the report delves into both math and reading, I chose to focus on reading, a subject in which students didn’t fall as far behind during the pandemic, but are now making weaker catch-up progress. Interestingly, the report was able to detect that reading recovery among older students in grades four through seven isn’t happening at school. They’re learning at a typical pre-pandemic pace during the school year but avoiding some of the usual deterioration of reading skills during the summer. Typically, students forget a lot over the summer, a phenomenon known as “summer slide” or “summer learning loss.” It is unclear from this report why students retained more than usual during the summer of 2022 and returned to school in the fall with better-than-expected reading levels.

I was more concerned about the alarm bells for third graders and why they’re struggling so much more than older students in reading. Timothy Shanahan, a literacy expert and a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said that younger elementary school kids rely on classroom instruction in school to learn to read. In older grades, much of the learning that accrues in reading is due to the students’ own reading and writing activity.

“Those [early] grades are particularly sensitive to educational disruptions,” Shanahan explained by email. “A fourth grader may have read for some number of minutes per day during those missed school days, while a kindergartner or first grader may not have been able to do that at all (since they wouldn’t know how yet).”

The early elementary years are critical because that’s when most children learn how to read words, what educators call “decoding.” Teachers in older grades don’t necessarily have the specialized training to backfill what students missed. A second grade teacher, for example, would likely not know much about teaching students how to identify and manipulate individual sounds in spoken words, an important step in learning to read called “phonemic awareness,” because it’s a skill that is the province of kindergarten and first grade teachers, Shanahan explained.

“I didn’t hear of lots of schools that were making explicit efforts to deal with that problem though certainly some individual teachers or schools might have,” said Shanahan.

Callie Lowenstein, a second grade teacher at a bilingual elementary school in Washington D.C., said that teachers feel “pressure” to stay on track with grade level lessons that don’t “accommodate or plan for the kinds of gaps we’re seeing.”

“Many curricula include an extremely cursory review of previous skills — so students who didn’t master earlier grades’ content are just left in the dust,” Lowenstein said. For example, the second grade reading lessons her school uses review the entire alphabet in one day and move quickly on. Many students need more practice.*

Catlin Goodrow is a reading specialist who works with third, fourth and fifth grade students who need extra help at a charter school in Spokane, Washington. She said she is working daily with a small number of third graders on basic first grade phonics. In some cases their parents kept them out of school for a full two years. But most students aren’t this far behind.

More common are random gaps because children didn’t receive enough reinforcement or weren’t taught topics during quarantines. One child might not understand how a silent “e” at the end of a word affects pronunciation. Another child might not understand how to sound out words with “ough” in them.

“It’s not as simple as being a year behind,” Goodrow said. “That would maybe be easier. It’s that they each have these really specific things that they didn’t pick up on. They each missed crucial bits and pieces.” Discovering them and filling them in for each child isn’t easy.

Goodrow is hearing from third grade teachers that even children who can read words are having a much harder time paying attention to what they are reading than in previous years. Third graders are having greater trouble absorbing the meaning, identifying the main character or explaining what the story is about.

“The comprehension piece can be something they’re having challenges with,” said Goodrow. “I often think about, ‘Did they get those experiences where they were having their teacher read aloud to them and think aloud, and they’re on the carpet nearby?’ A lot of times, even when they were back at school full time, they were distanced. So they might not have had some of those early literacy experiences that built their ability to focus on the text that they’re reading.”

Because third grade is so critical, 16 states plus the District of Columbia require children to repeat the year if they cannot read at a basic level. Based on this NWEA test score report, states could be facing an avalanche of held-back children if those retention rules are enforced later this school year. That’s something I’ll be watching.

*Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Callie Lowenstein as a New York City teacher. She now teaches in Washington D.C.. In addition, Lowenstein does not follow the curriculum used in her school and gives her students more review when needed.

This story about third grade reading was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

Third grade is the year students transition into fluent reading. I wonder to what extent lost opportunities to foster reading fluency have contributed to this concern. Fluency has been called, and still is, “the neglected reading goal.”